Manea, Maria-Gabriela, "How and Why Interaction Matters: ASEAN's Regional Identity and Human Rights" Cooperation and Conflict, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 27-49, Mar 2009

Christopher Hemmer and Peter J. Katzenstein, “Why is There No NATO in Asia? Collective Identity, Regionalism, and the Origins of Multilateralism,” International Organization, Vol. 56, No. 3 (Summer 2002), pp. 575 - 607

Nishikawa, Yukiko, "The "ASEAN Way" and Asian Regional Security," Politics & policy 2007 35, 1 42 -56

Ruukan Katanyuu, "Beyond Non-Interference in ASEAN: The Association’s Role in Myanmar’s National Reconciliation and Democratization," Asian Survey December 2006

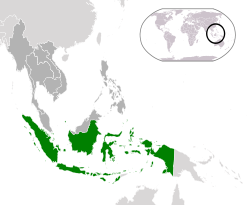

I should probably add that I was utterly unaware of which countries are in ASEAN. I knew Malaysia and Indonesia, and kind of assumed that some of the other nearby ones (Brunei, Singapore) were in it, but I did not know that the Philippines were a founding member, nor that ASEAN had expanded to include what used to be known as Indochina. (Does the peninsula itself have a name?) I feel really dumb for not knowing that, and I know the internet is not the place to admit ignorance on things that basic, but there you go.

On to the readings:

Hemmer and Katzenstein: There was little here that was all the surprising to me. Really, the US treated SEATO and NATO differently because of (basically) racism? Not really a shock. They do a good job putting together all of the data to show that the US treated multilateralism differently in Southeast Asia and the "Atlantic Community" simply because the US saw itself as a descendant of Europe, and saw Asians as savages, but I think the general idea should be pretty obvious. I did find the idea of creating these regions basically out of linguistic cloth interesting, as well.

Nishikawa: I knew little of ASEAN's general work in the region, so this was useful for understanding how ASEAN deals with problems among its constituent states. I find it really interesting (and will come back to this with a different reading) that states who feel such a need to create a supranational organization also feel so jealous of their sovereignty. I also think that more emphasis on "management" of issues, rather than "resolution," could be useful around the world. If our goal is to stop people from dying, it would probably help to start with that as our base, rather than a comprehensive solution that ends the dispute once and for all.

Manea: This one was extremely theoretical, and it was difficult for me to wade through. However, it really helped to set some of the stage for me with Nishikawa. I am, of course, ecstatic to see these rising powers (and yes, obviously Indonesia and Malaysia are rising powers, and I dare say Singapore is already a middle power, at least economically) take such a keen interest in human rights. More than that, though, is the way that the democratization impulse has changed the nature of the organization. The democratizing powers (Thailand, Indonesia, Philippines) have left behind the legacy of colonialism, to a large degree, and are now willing to stand up and require more of others. This changes the organization from a way to avoid colonial interference to instead do real good. I like that.

Katanyuu: This is really just a case study of how ASEAN has interacted with Burma since inviting Burma to join, and in particular how it has come to allow itself to push Burma on what had previously been seen as "internal affairs". This was by far the clearest expression of how ASEAN used to work, and how it has changed. Of the four, it is by far the one I'd recommend most for someone interested in this subject.

Next week will be ASEAN's actual military affairs, which I think I will have more comments on.