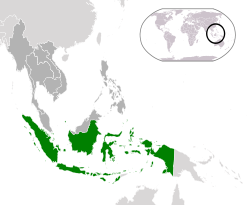

This week, the topic is Indonesia. I will confess, I know a lot less about Indonesia than I do the other countries surveyed so far. My academic focus has long been Northeast Asia (specifically the Chinas and the Koreas), and so the rest of the course will involve a lot more eye-opening for me.

The readings this week are:

The discussion papers focused squarely on the Indonesian military reformation that has taken place in the last decade as Indonesia moved from authoritarianism to democracy. In the authoritarian period, the military was used primarily as a means of social control and regime legitimacy. Moreover, military officers held most of the commanding positions in the government (including for most of the period the Presidency, after General Suharto overthrew Sukarno in a coup.)

Because of the size and its designation as the world's "largest Muslim country," I assumed that Indonesia had a military commensurate with its status. However, apparently at this point Indonesia spends less than 1% of GDP on its military, and many military leaders consider it far too small to defend the country (and particularly all of the important waterways in the country). The military in total has less than 400,000 troops, the vast majority of which are ground troops. This boggles my mind, as an island chain would seem to need a navy far more.

However, when looking into the internal workings of Indonesia, it begins to make more sense. The overriding threat to Indonesian sovereignty does not lie in the pirates in the waters, or even in naval attack by neighboring states. Instead, it is insurgency, guerrilla warfare, and terrorism that concerns the defense department of Indonesia, though it seems that this does not worry the policy makers as much as the possibility of the military attempting to take back its old role as political masters.

There is a good chance that overall defense spending will increase, if only to increase professionalism and to decrease the military's reliance on military-owned companies. These companies are largely seen as an obstacle to a truly professional military and a potential for extreme corruption. The very idea boggled my mind when I first saw it, for that very reason.

The last major topic of the discussion papers was the war on terrorism within Indonesia, with strong disagreement about how that war should be prosecuted. Two writers (Adrianus Harsawaskita and Evan A. Laksmana) expressed strong skepticism that the military was fighting terrorism for any reason other than as a pretext for re-establishing some of the power it had given up in the last decade. Robert Eryanto Tumanggor instead pushes for more democratization and more respect for legal rights as a partial method toward resolving the grievances that lead to terrorism. Lastly, Sapto Waluyo echoes Tumanggor, but stresses that the problems are systemic to the government, and require diligent reform.

The other piece (from Small Wars Journal) was much more focused on the problem of guerrilla warfare in Indonesia, a country that was both founded on guerrilla warfare and has fought more COIN campaigns than most. I was impressed that one of the founders of the Indonesian state wrote not only a handbook to guerrilla warfare (like Mao and Giap both have), but also within that same book a COIN manual. I believe that may better show the difference between Indonesia and other countries in the region. Because Indonesia is an amalgamation of many cultures and ethnic groups, the legitimacy of the regime is always in much more danger than the regimes in Japan, Korea, China, or Vietnam. Indonesia is a modern invention, born (mostly) out of colonialism, and as such faces dangers quite different from its neighbors. Moreover, these dangers compound each other; a lack of legitimacy fuels terrorism, which fuels military overreach, which lowers legitimacy further. With all of this in mind, it is remarkable that Indonesia has managed to achieve the degree of stability that it has.

No comments:

Post a Comment